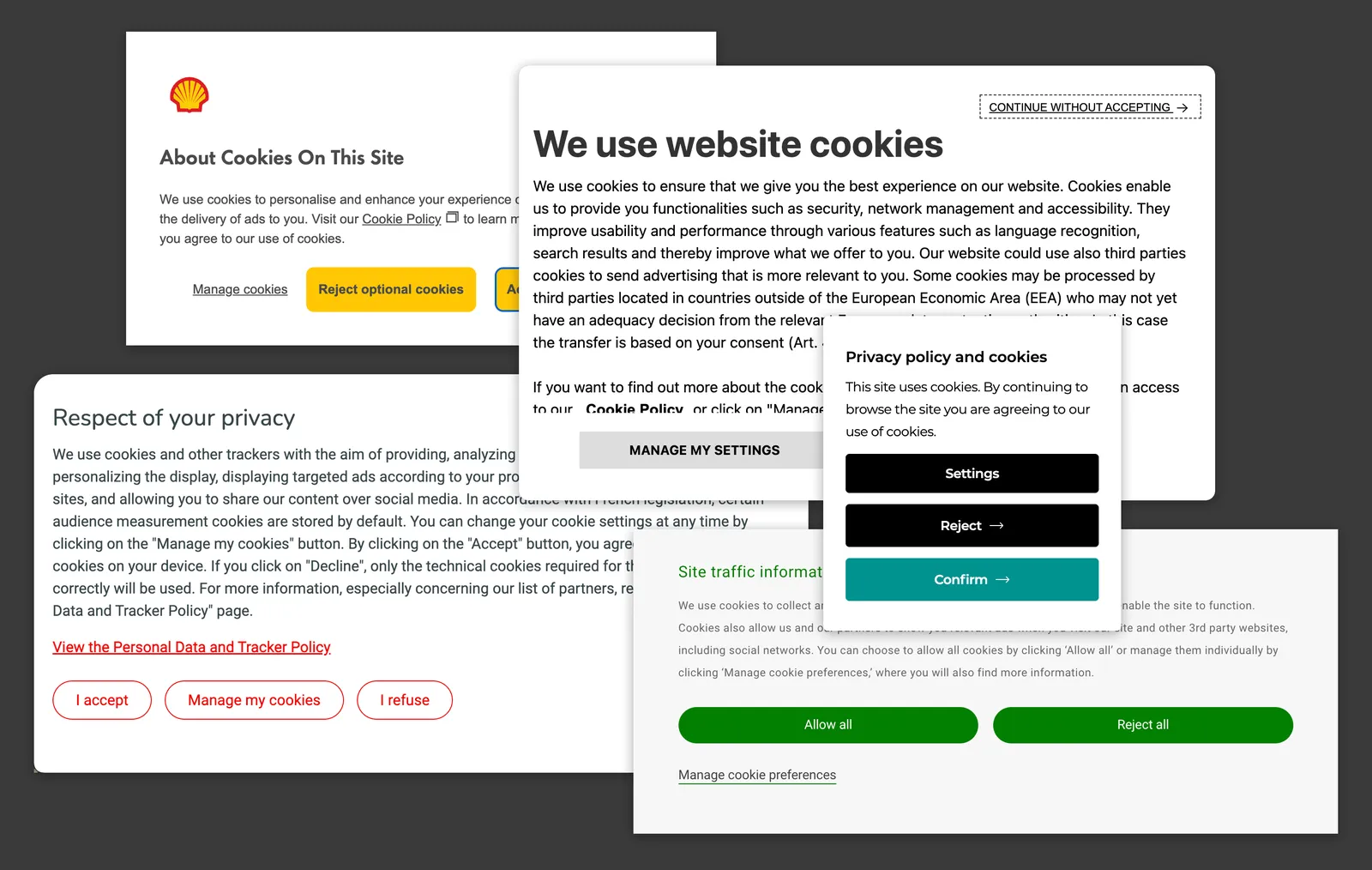

If you want to know the future, look to the present. For this prediction, consider the current state of GDPR cookie consent banners and dialogs.

I’m going to let you in on a little secret here: You don’t actually need to use a cookie consent notification.

Sites in the European Union (EU) that only use first party cookies—or no cookies at all—don’t have to display a message informing the people visiting their site. This is because the information the site collects is not distributed to advertisers, data brokers, and other less-than-savory services and individuals.

So, what does this have to do with digital accessibility?

Compliance

The prevalence of cookie consent notifications demonstrate what organizations are unwilling or unable to do: Prioritize the people who use their services in the face of regulation.

Here, I’d like to call attention to the cottage industry of for-profit third party services that popped up to make turnkey solutions for consent management. These services arose because organizations could not, or would not get their house in order in time for the regulation’s deadline.

These managed solutions also may have difficulty delivering what they promise. This is to say nothing of the lack of accessibility with their underlying code.

The emergence of cookie consent UI as a service signals a potential future for digital accessibility. Here, know that the compliance deadline for the European Accessibility Act (EAA) has already passed.

The EAA deadline passing means that organizations in the EU, or who do business in the EU, are now responsible for ensuring their web presence is accessible. And like with data privacy, most organizations are found wanting.

The lay of the land

Digital accessibility has been pushed to the margins for about as long as there has been a widespread, public internet. The majority of businesses simply fail to make it a priority, despite evidence that they’re leaving an incredible amount of money on the table.

Employee reward structures at most for-profit organizations do not incentive investing in accessibility. In addition, mainstream design and development education don’t cover accessibility practices unless you’re extremely lucky.

This creates an environment that is rich for exploitation. We have already seen the beginnings of this in the form of accessibility overlay companies, which prey on fear and ignorance to peddle deceptive, ineffective, and harmful products.

Additionally, EU-based studios and consultancies are now scrambling to assure their current and prospective clients that they are experts at accessibility. This will likely lead to looking for easy answers in a space that is choked out with misinformation and astroturfing from bad actors.

The third leg of this stool is the push to use LLMs for code generation. They are trained the web’s source code, and it is an uncomfortable truth that this code is largely inaccessible. This will serve to further enmesh and encode inaccessibility.

What does this have to do with accessibility in design?

There will be concerted efforts to “solve” accessibility on the performative, contractual layer. This is in opposition to doing the in-the-trenches work to actually remove barriers.

Much as how cookie consent banners spotlight organizations that are unwilling to prioritize privacy, “contractual” accessibility communicates the abdication of care.

In the practical, this means designers will have more LLM-based features integrated into their tooling. These tools will promise to do their job for them under the guise of cost savings and risk mitigation. This will further widen the divide between the work and its human-facing impact.

The same phenomenon applies to every other discipline involved with creating digital experiences that is currently experiencing pressure to adopt LLM-based tools.

Automated tooling will also indirectly or directly communicate accessibility is something you don’t have to worry about. This isn’t a stretch by any means—consider how so many other things LLMs claim to handle are framed as annoyances or drudge-work.

The gap between contractually-guaranteed accessibility and actual intuitive, usable, and accessible experiences will widen. Bias-perpetuating, solutioneering automation will serve as a wedge to widen this gap.

The compelling of use of general use LLM-powered tooling will also only further move the Overton window away from pointing out generated access barriers. It will also distract from tackling the root problems that need to be addressed in order to enact meaningful change.

It doesn’t have to be this way

Despite all this, people don’t sue because a site violates the EAA or WCAG. They sue because they can’t use something.

All the song and dance that serves to abstract away making experiences actually usable does not count for anything if someone can’t operate a service to get what they need. It’s the same as legal action due to managed cookie consent banners that don’t actually honor your privacy choices.

The majority of access issues are created on the design layer. The EAA is a powerful force for enacting change. Why not do what you should have been doing from the start? Bake proactive accessibility considerations into all aspects of your organization—including design.